Chances are that many of you reading this will already be familiar with the Melt the ICE Hat pattern by Paul S. Neary. At the time of writing it’s still sitting atop Ravelry’s “Hot Right Now” list, three weeks after publication. There are over 7,300 linked projects (already 700 more than when I checked two days ago) and the momentum shows no signs of stopping. I don’t think I’ve ever witnessed such a phenomenon in the nearly 18 years I’ve been on Ravelry. Given the inspiration and the history behind this pattern, I felt compelled to write about it here.

The hat pattern is a fundraising effort by Twin Cities-area yarn store Needle and Skein, with the proceeds going toward immigrant aid agencies who will distribute the funds to those impacted by ICE. Their description of the pattern on the Ravelry page is as follows:

In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design. (source)

I don’t know if anyone at Needle and Skein has Norwegian heritage or other connections to Norway, but the Twin Cities are known for being one of the hubs of Norwegian immigration in the 19th century, so the use of a symbol of the Norwegian resistance in this current moment is apt. And they’ve caught the attention of the Norwegians, too: last weekend the national broadcaster NRK’s weekend news radio show Helgemorgen featured a segment called “symbolic resistance in knitting and music,” where the Melt the ICE Hat was discussed alongside Bruce Springsteen’s new song “Streets of Minneapolis.”

Red hats were in fact both worn as a symbol of resistance and subsequently banned by the occupying forces in 1942.

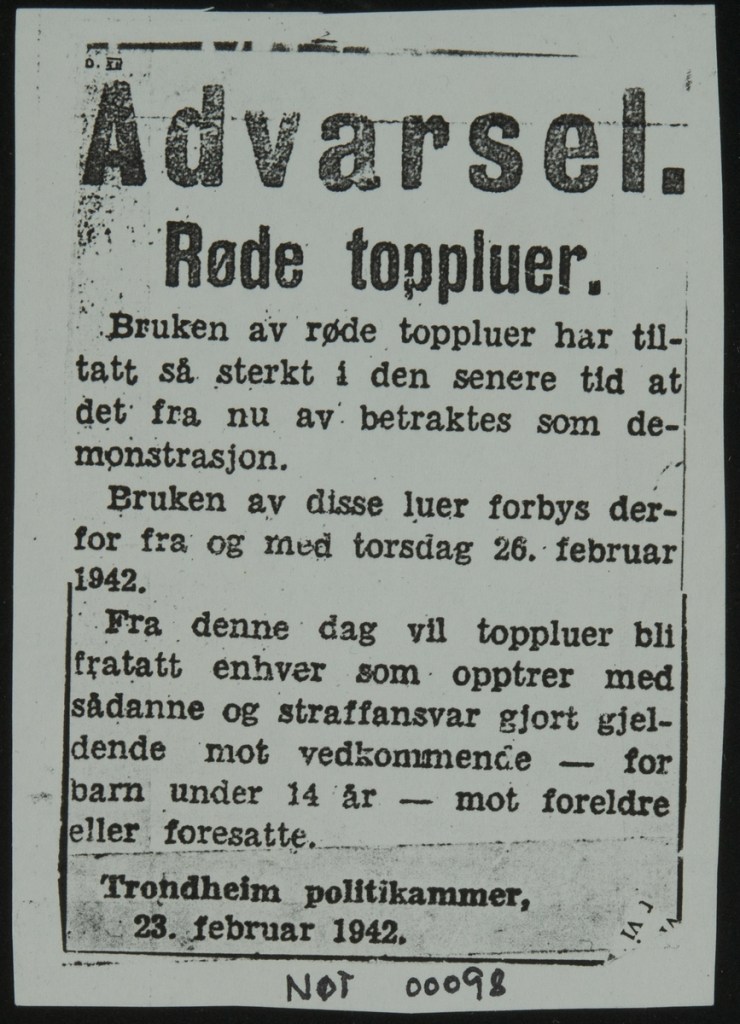

The above notice was published in the Trondheim newspaper Adresseavisen on February 23, 1942. It reads:

Warning.

Red hats.The use of red hats has increased so much in recent times that it is now considered a form of protest. The use of these hats is therefore prohibited as of Thursday, February 26, 1942. From this day on, hats will be taken away from anyone who appears wearing them and criminal liability will be imposed on the person concerned – for children under 14 years of age – against parents or guardians.

Trondheim Police Department, February 23, 1942.

This followed from an earlier ban in December 1941 on the use of the Norwegian flag or the flag’s colors in clothing, decorations, trademarks, or advertising (according to the Norwegian Folk Museum).

A few examples of these hats can be found in the digital collections at digitaltmuseum.no. Some are from the time of the occupation, while others are older examples that show that this type of hat has a longer history and a deeper relationship with Norwegian identity.

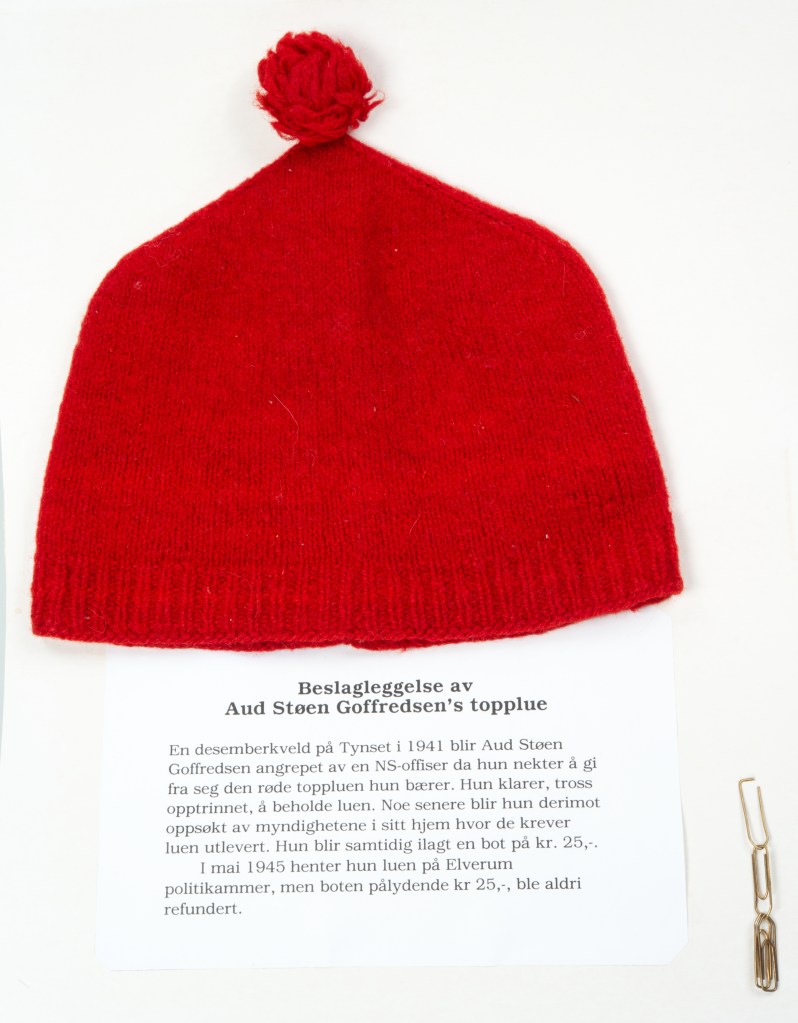

The above example belonged to Aud Støen Goffredsen, who refused to remove the hat when ordered to in 1941. The authorities later came to her home to confiscate the hat and issued her a fine of 25 kroner (around 785 Norwegian kroner or roughly 80 USD today). She was able to reclaim the hat from the police station in May 1945, at the war’s end. This display case from the Anno Museum in Nord-Østerdalen also contains several paper clips, which were worn in buttonholes as another way to signal resistance to the occupying Nazi regime.

Older examples in museum collections show that rød topplue was closely associated with the fishing industry in the 19th century, and it went by many different names depending on the region; raudehue in Sunnmøre, lofothuve in Lofoten. An example from Sunnmøre was recreated in the book of patterns Rett i garnet by Line Iversen and Margareth Sandik (published in English in the US with the title Fishermen’s Knits from the Coast of Norway – A History of a Life at Sea and Over 20 New Designs Inspired by Traditional Scandinavian Patterns) as the Fladen hat.

These hats were also closely associated with the annual Lofoten fishery further north, as Mette Gårdvik and Ann Kristin Klausen show in their article Tre røde toppluer. The article includes a painting based on a photograph (as well as the photograph itself) in which a group of men are pictured in the middle of gutting cod, each one wearing a pointed red hat.

The link between the knitted red hats and Norwegian identity becomes even stronger when we look to modern folk costumes, which are often based on clothing from the latter half of the 19th century. Both the men’s Sunnmørsbunad (first created in the early 1900s) and the Haltdalsbunad (based on extant clothing from 1860-1870) feature knitted red toppluer.

Additionally, similar hats are closely associated with Christmas celebrations as the nisselue. When I first told my Norwegian coworkers about the Melt the ICE Hat and showed them a picture, their immediate response was, “it looks like a nisselue!” rather than thinking about the resistance. Interestingly, though, these two things (Christmas and the resistance movement) sometimes intersect, such as this example from the Sverresborg Folk Museum here in Trondheim. The description states:

“The hat was confiscated by German police in 1942 when Synøve used it at school (Trondhjems Borgerlige Realskole). Synøve demanded her hat back, which she received when she went to the police station. The hat was later used as a julenissepynt (Santa decoration).”

The ban on red hats also had implications for Christmas imagery during the war. This post from the Norwegian Folk Museum in Oslo discusses the dilemma for Christmas card artists during the war, with several examples of cards featuring nisseluer in less traditional colors, like green, blue, or yellow. The post is written in Norwegian, but the cards are interesting to see even for those who don’t speak the language. Prior to the ban (or even after it went into effect, in some cases), some artists chose to provoke, as in the example below, which proclaims, God norsk jul! (Merry Norwegian Christmas!). The post about the card on Digitalt Museum notes that this card was part of a collection of ten, all of which declared a merry Norwegian Christmas in order to be deliberately provocative under the occupation.

This brings us (somewhat) full circle back to the resistance movement during the second World War. Given the ban on using the colors of the Norwegian flag in clothing that came first, it’s not a surprise that Norwegians wanting to show symbolic rejection of the occupying regime would turn to knitted red hats. The most prominent color of the Norwegian flag is red, the hats were easy for people to make for themselves or their loved ones, and these hats were an existing part of the clothing culture of Norway, already linked with Norwegian identity. There was also precedent for the use of red caps as a symbol of resistance or liberty, such as the French bonnets rouges, the Phrygian caps worn by revolutionaries during the French revolution.

While some social media posts about the Melt the ICE Hat feature comments bemoaning the color (red being the color associated with the Republican party as well as bringing to mind MAGA hats), other commenters indicated that they saw the hat as a way to reclaim red, or to be provocative. Some comments followed up with the fact that it doesn’t matter what color you use to knit the hat, because if you’ve purchased the pattern, you’ve financially supported the Needle and Skein fundraiser for immigrants affected by ICE. And that’s what it comes down to. Support for each other, for protecting the most vulnerable in our communities. Let it be remembered that when people came together to resist, the Nazis lost.

—

The top image is the original image of Paul S. Neary’s Melt the ICE Hat, from the Ravelry pattern page.

Leave a reply to Diane Prager Cancel reply